Lucas Glockner, the builder and first landlord of 97 Orchard Street, immigrated from Baden, Germany in 1843, at age 23. He becomes a citizen of the US just six years after his arrival, in 1848. With his first wife, Catherina, he has three children: Edward, Johan, and Louise, and works periodically as a tailor.

In 1863, 20 years after his arrival to New York, he invests in real estate with two other men. Together they buy one lot of land on which to build three buildings—95, 97, and 99 Orchard Street–each man owning one building. Glockner pays to construct 97 Orchard Street, becoming the first owner and landlord of the Museum’s flagship historic tenement.

Photo: Tax photograph of 97 Orchard Street in 1940. Collection of New York Municipal Archives.

By a year later, in 1864, Glockner has remarried after the death of his wife and is living in 97 Orchard Street. In the end, Glockner was not only building his business, but his home as well.

During the 20 years between Glockner’s arrival in New York and the time he built the tenement at 97 Orchard Street, medical professionals and city officials in London and New York were slowly gaining information that begins to change understandings about the cause of disease. The understanding of the connection between cleanliness and sickness was only just emerging for medical professionals, so while it’s unlikely that Glockner had this direct knowledge, his choice to install flush privies and fresh drinking water would slightly improve residents’ health outcomes compared to buildings without these features.

In the backyard of 97 Orchard Street, Lucas Glockner paid extra to have the outhouses drain into the sewer system, and to have a water spigot that brought water from the Old Croton Aqueduct (still a source of the city’s water today).

Photo: Tenement Rear Yard in 1902 taken by New York’s Tenement House Department. Collection of New York Public Library.

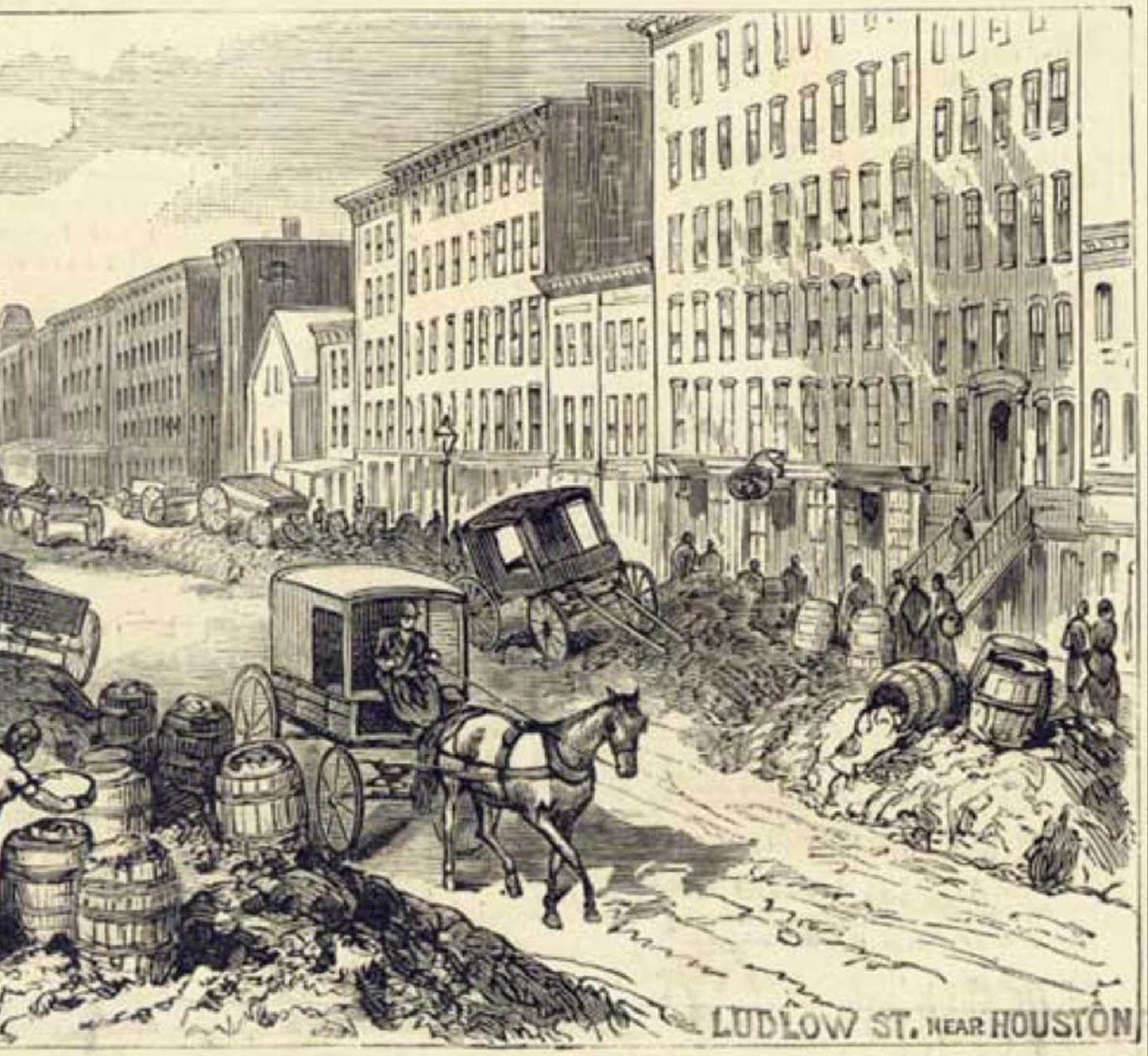

As today, our housing options and our access to healthy environments can shape our experience during a public health crisis. The tenement house at 97 Orchard Street was constructed just prior to health reforms. The residents of its 22 apartments worked hard to keep their homes clean–an endless task given the condition of the streets and sidewalks of the 1860s.

In the absence of a municipal department of sanitation, household and commercial waste collected in piles on the public sidewalks alongside mounds of horse manure accumulating in street gutters. Residents of the lower wards, like the Lower East Side, would have had to trudge their way through streets piled three feet high with garbage in many places.

Photo: Ludlow Street Near Houston. Late 19th Century. Source Unknown.

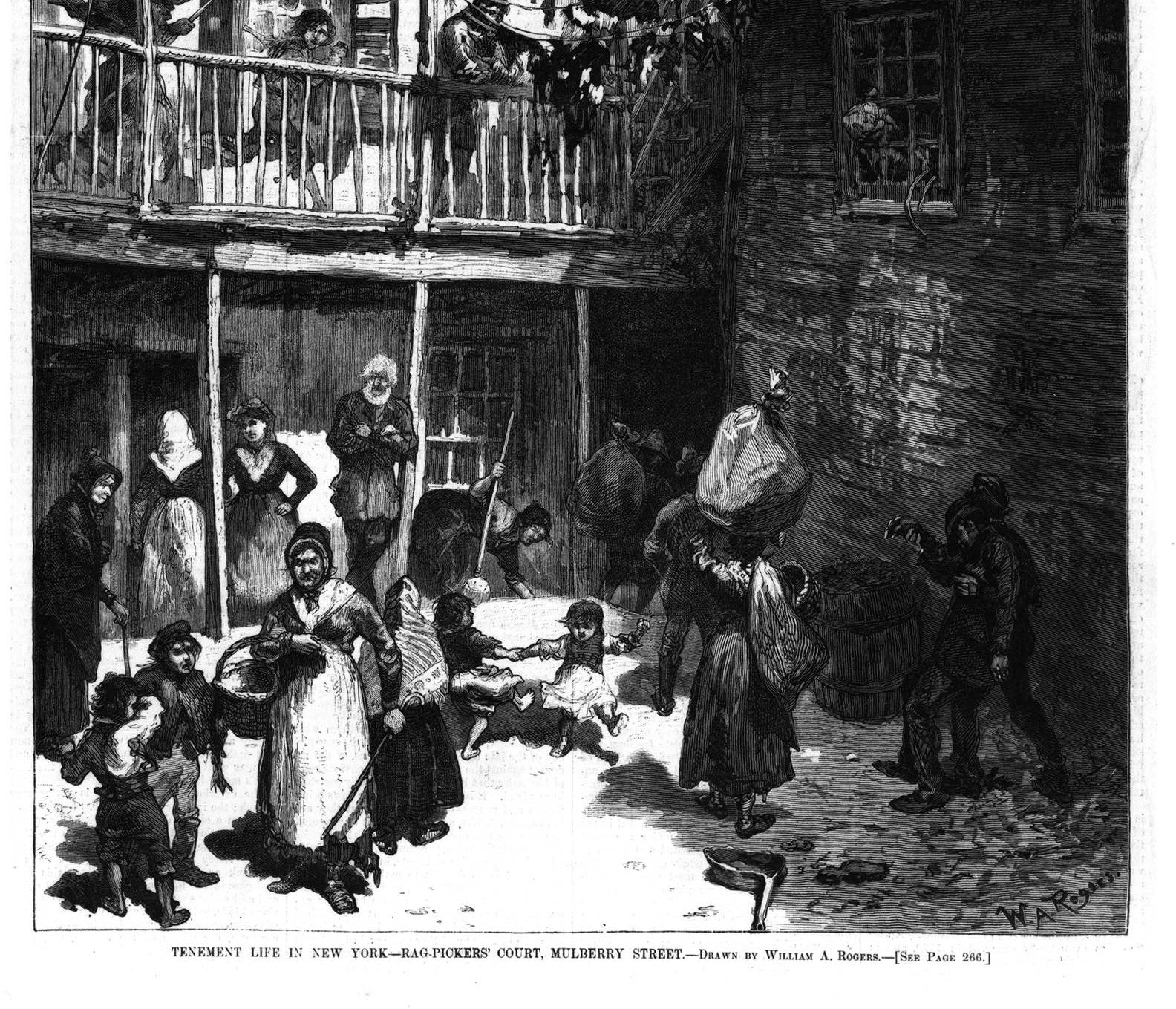

The street presented clear and literal health obstacles for Lower East Side residents, and tucked away in the rear yards of these tenement houses lived a more subtle and yet potentially lethal danger. Residents, shop owners and, in some cases, shop customers made frequent use of the rear yards, as they provided access to water and the privies.

The rear yards of mid-19th to early 20th-century tenement buildings stood at the intersection of the private space of the home and the public world of the street. The rear yard served as an extension of the tenement household, helping residents with their cooking, cleaning, laundry washing, and bathing; it also served as a facility for the disposal of human and household waste.

Photo: “Tenement Life in New York – Ragpickers Court, Mulberry Street.” Harper’s Weekly 1878. Collection of the Tenement Museum.

An excavation of the rear yard at 97 Orchard Street in 1991 unearthed the exact features built by Lucas Glocker in 1863. The uncharacteristically advanced amenities as compared to the average tenement house in 1863–namely the slate paving stones, flush privies (school sinks) and fresh drinking water from the Croton Aqueduct—would be noted by health inspectors in the coming years.

However, the lag in scientific understanding of diseases and their cause meant that while the conditions of rear yards became the focus for reformers and city officials in the 1860s, there were judgments and stereotypes of immigrants and newcomers embedded in their reports and recommendations.

In the below quote, J.T. Kennedy, a health inspector for the district that included 97 Orchard Street commented on the changes in the neighborhood, tying them specifically to decisions of German residents like Lucas Glockner.

“This part of our city at one time was inhabited by some of our most respected citizens of moderate ideas, confined to houses of two stories in height; but time has changed the whole character of the inhabitants. The Teutonic race seems to have rushed in here in sufficient numbers to predominate, and landholders have found it profitable to erect very many substantial tenant-houses, to accommodate the increase of the population”

– Dr. J.T. Kennedy

Inspector for the Eighth Sanitary Inspection District, in which 97 Orchard Street stood.

Next, we explore how a rear yard like the one at 97 Orchard Street can help us trace the shifts in understandings about illness during the 19th Century.