Did you fill out the 2020 Census? Ever wonder how that information is used?

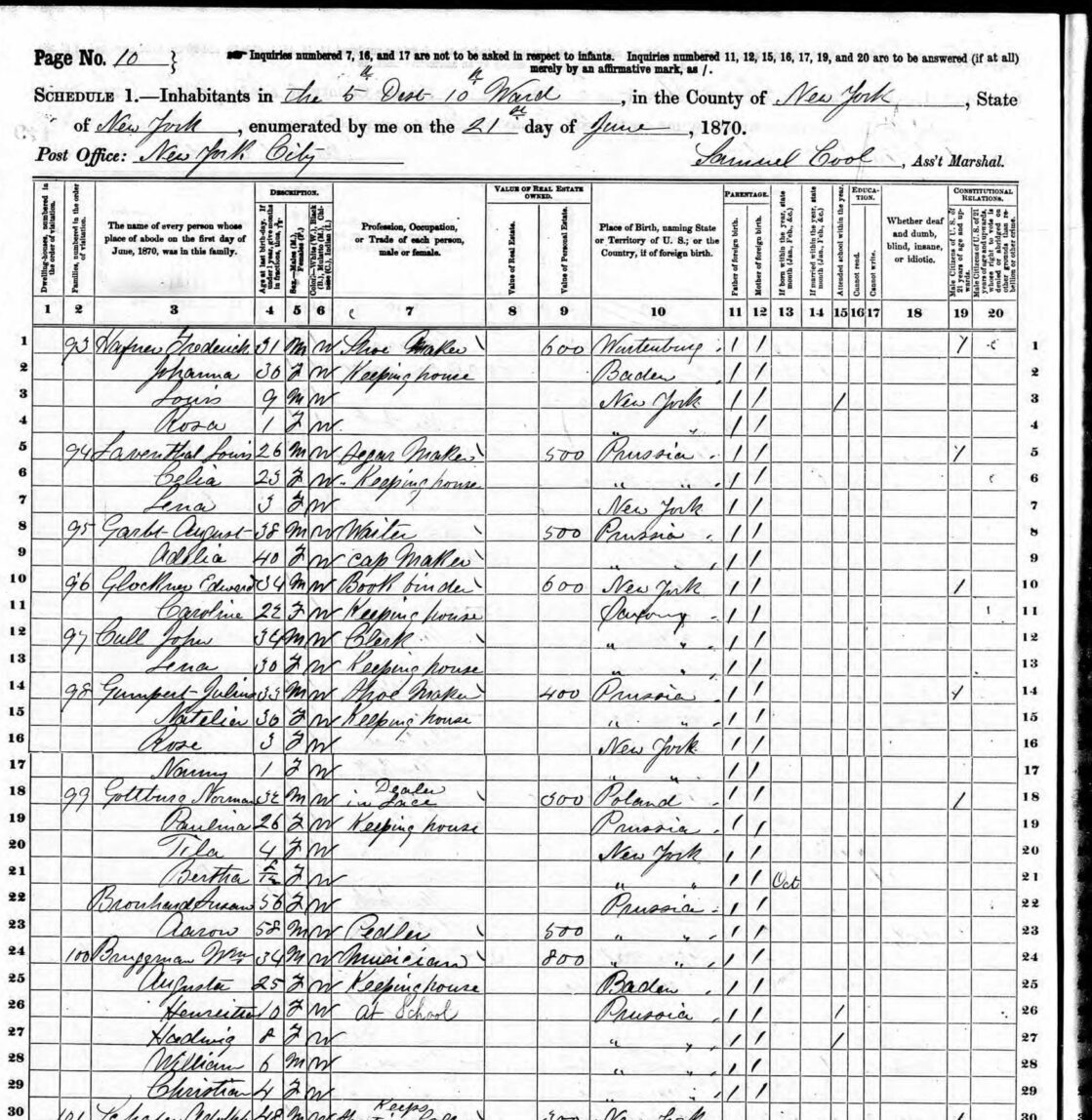

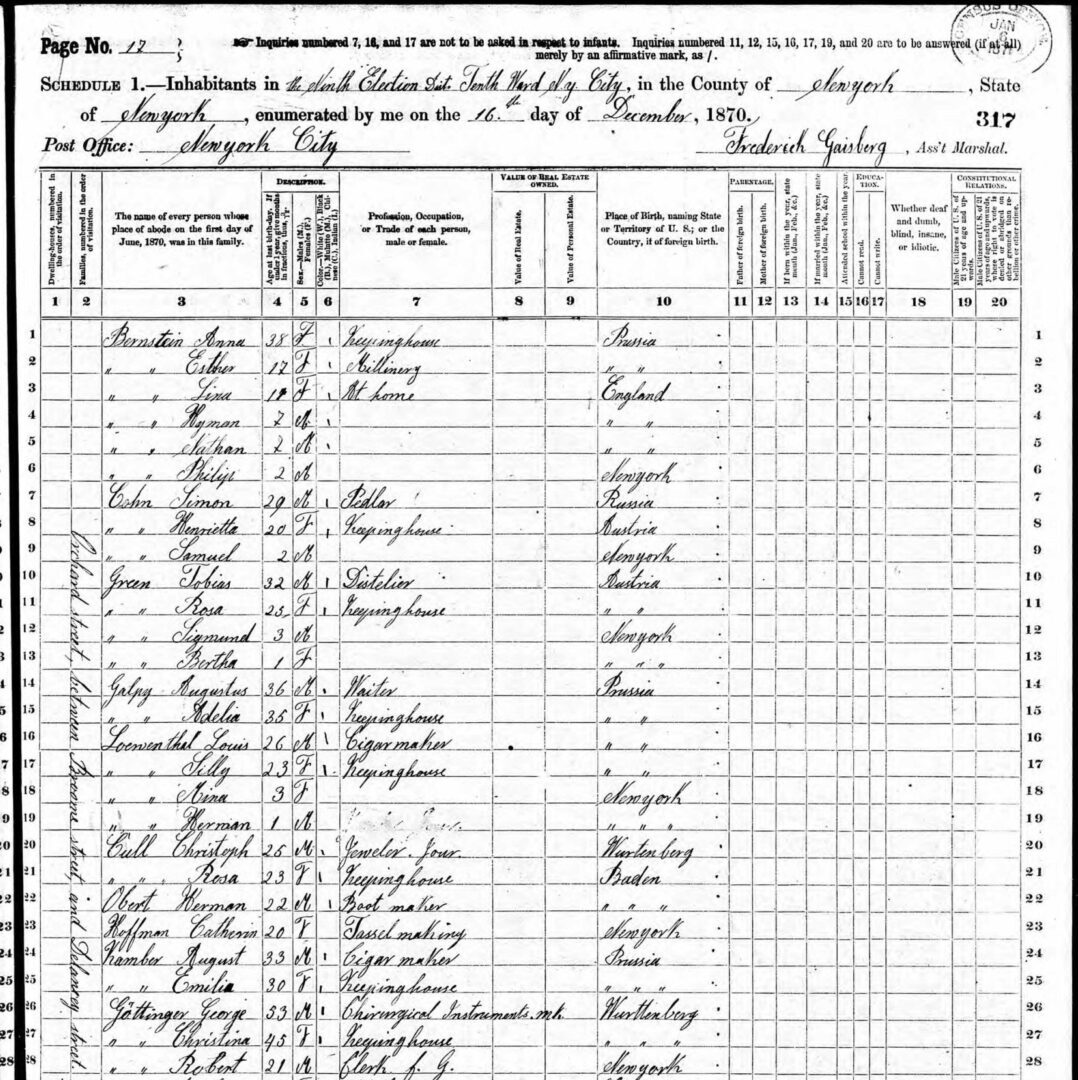

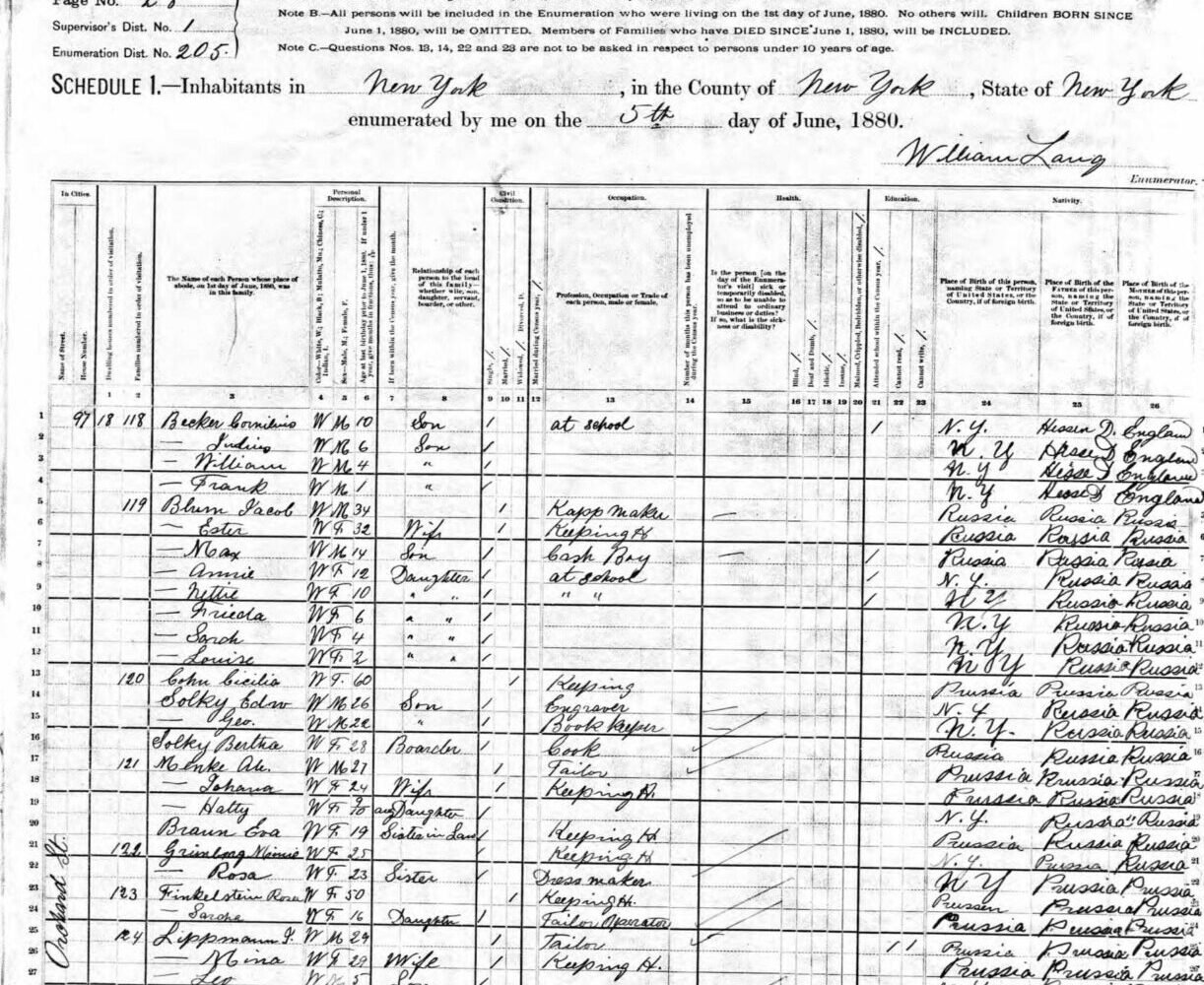

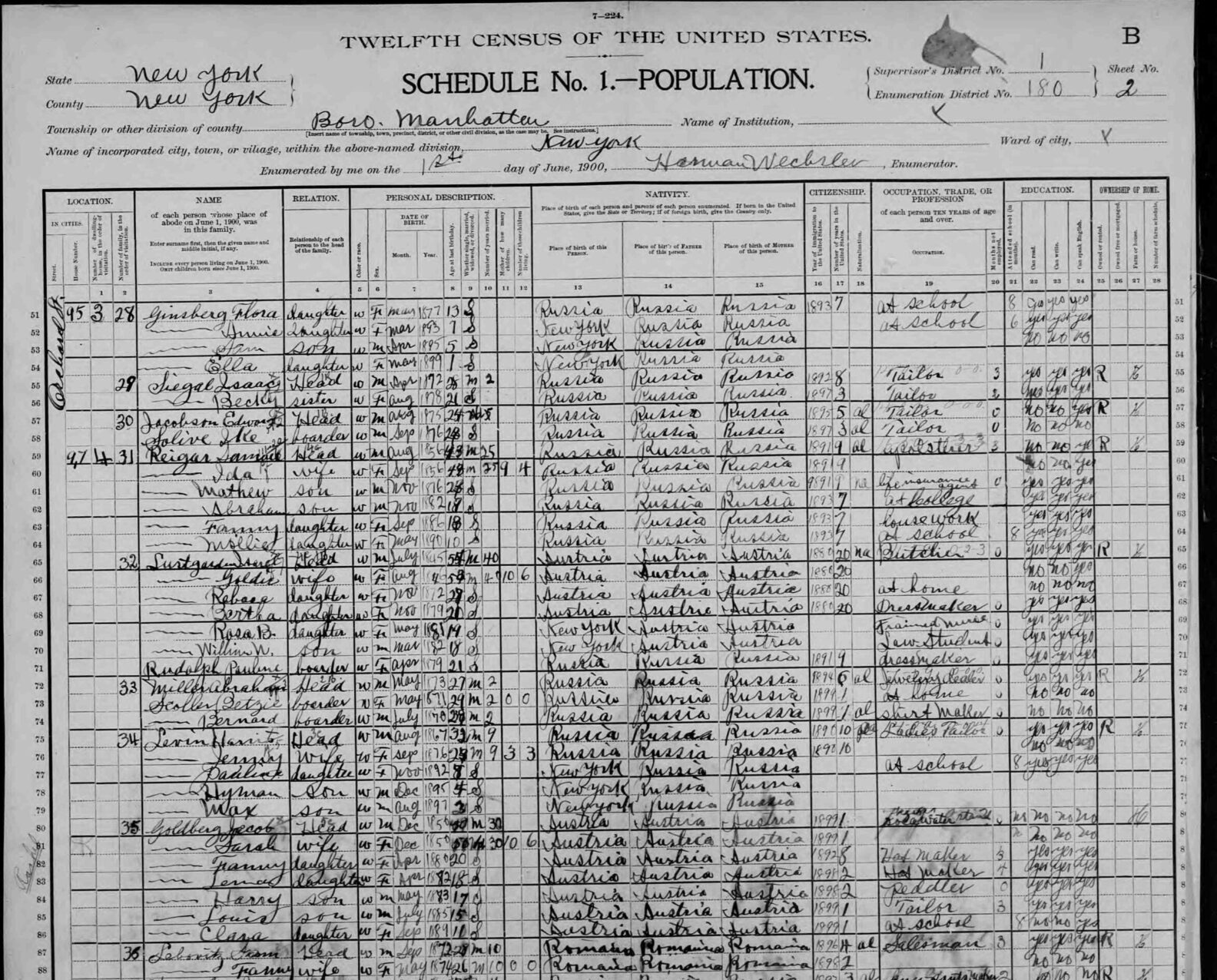

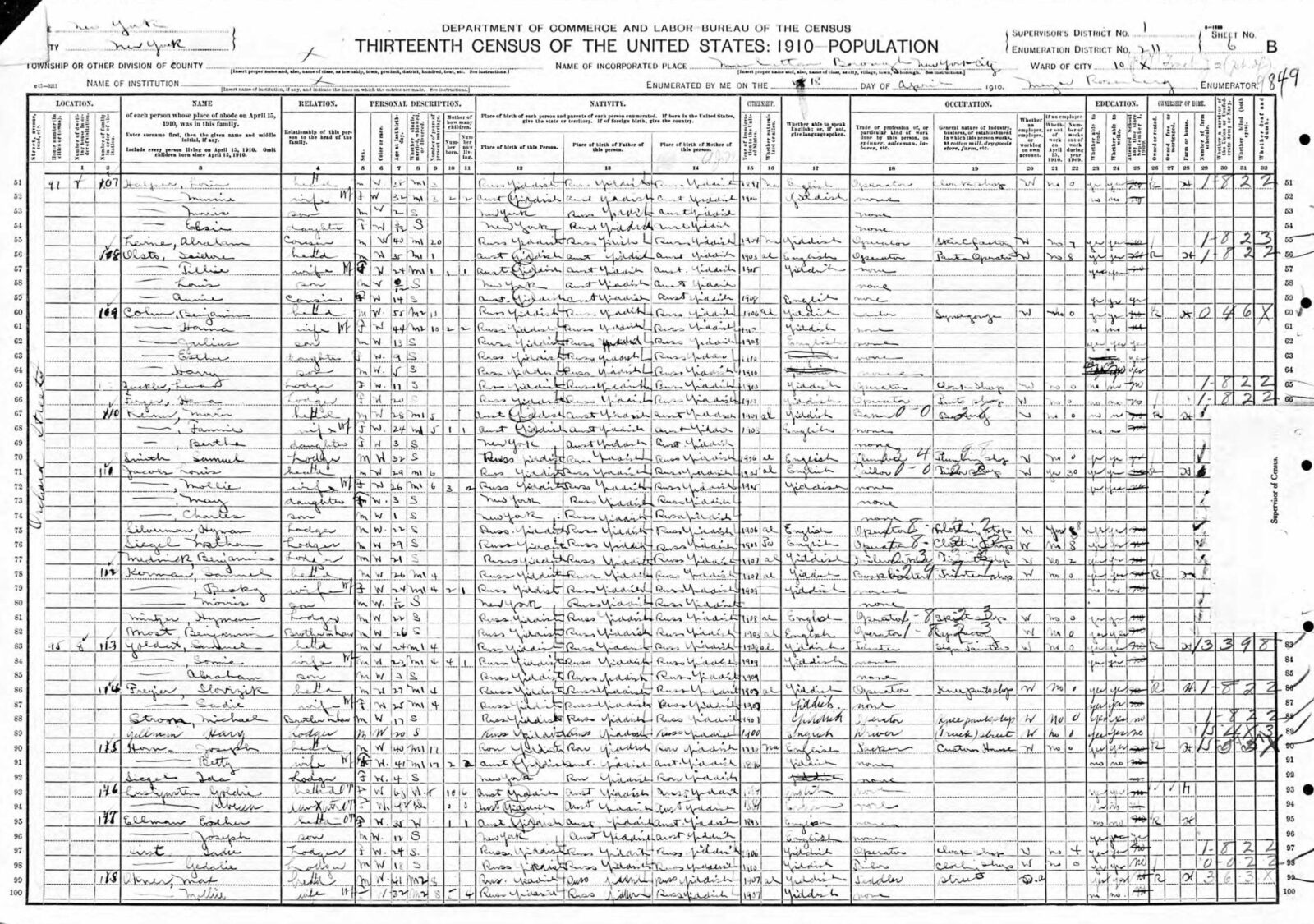

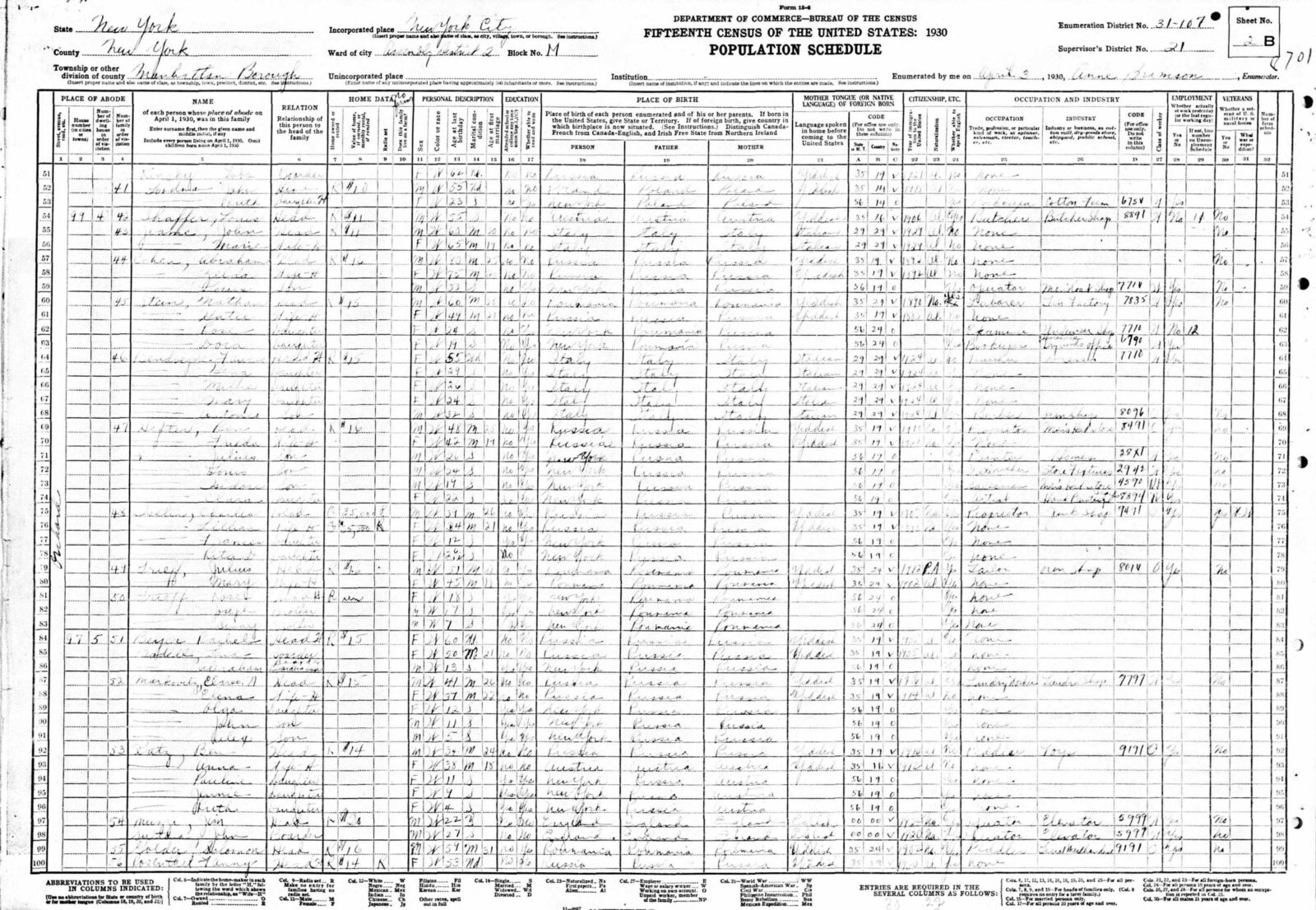

In addition to being essential for political representation and deciding federal funding, census data is crucial for historians. But to protect people’s privacy, historians can’t access census data until 72 years later. Every 10 years, another census record becomes available for the public to access. On April 1,2022, NARA released the 1950 census data and for a museum dedicated to public records research, this is especially important.

In this digital exhibit, use an interactive timeline to get a behind-the-scenes look at how our Museum historians have used the census to learn how residents of the Lower East Side lived.