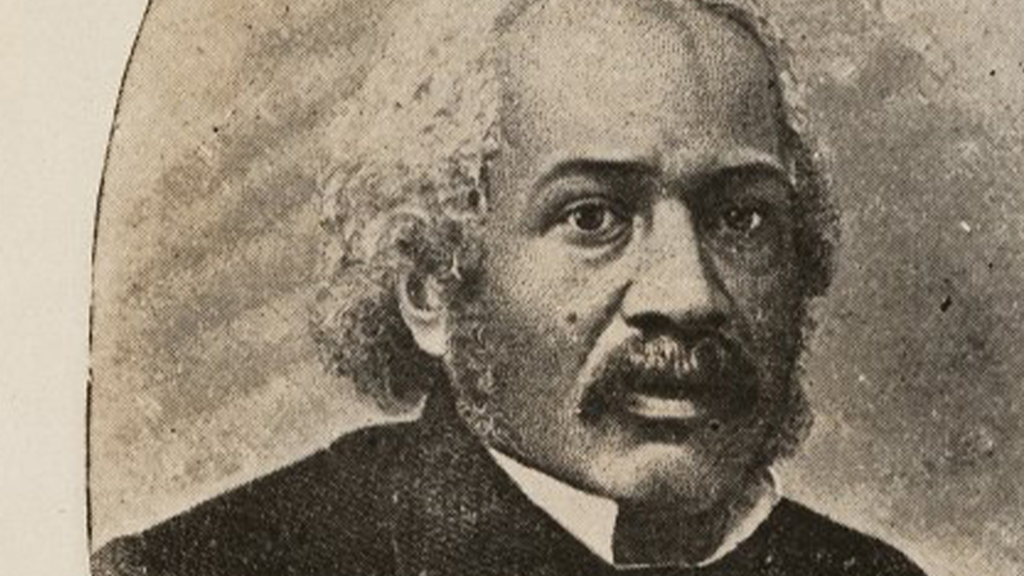

One of his more famous works – part of which the Tenement Museum relied upon when recreating our new permanent apartment exhibit – was a series of essays published in Frederick Douglass’s Paper from 1852-54. Titled “The Heads of the Colored People”, these essays highlighted the lives of working-class Black New Yorkers, from boot-blacks and washerwomen to editors and schoolmasters. These were written at a time when labor and class issues were extremely topical in Black communities, particularly in emancipated New York. People were discussing what it meant to be an enslaved laborer versus a free laborer, and what the concept of “labor” even meant as the nation moved towards industrialization.

Dr. Smith argued implicitly and explicitly that all forms of labor are respectable and meaningful. This was the opposite of Frederick Douglass’s opinion on the subject, who believed that the only path forward for Black communities was moving towards “skilled” labor. But Dr. Smith understood that it was important to respect the laborers in these lower-level positions, not just because they were doing essential work that needed to be done in communities, but because for some people, doing that work and doing it well was important, and a source of pride.

His essay, “The Washerwoman” was inspirational for the Tenement Museum because it’s one of the few resources that vividly describes the inside of a Black tenement home of this era. Although not stated outright, some historians believe that the washerwoman in this story is inspired by Dr. Smith’s mother. The washerwoman in the story is cleaning clothes near the stove while her young son is reading nearby. It vividly describes the physicality of the work, the repeated noise of her beating the clothes, the strength and sweat involved, her previously payment of a turkey carcass resting in the larder.